There’s nothing like giving Mother Nature a good flirt. All it takes is some concrete, steel rebar and pair of knockers to stare defiantly at the great matron and say with bravado, “there’s no way you’ll ever smite us wench.”

Just ask the engineers down in New Orleans. Or more locally, the engineers at the

Hudson River Black River Regulating District, who recently admitted that the Great Sacandaga Lake has crested more than

two and a half feet over the spillway at the

Conklingville Dam.

For those unfamiliar with dam spillways, the damn regulating district or New York’s largest manmade reservoir, that’s a record water level after more than 75 years of monitoring them. More poignantly, however, that’s nearly six feet above the level when the reservoir is ordinarily considered full.

While having an extremely high water level ruins nearly all recreation on the lake, it doesn’t necessarily bother any of the downstream municipalities, such as Luzerne, Corinth or Glens Falls. Count Fort Edward, Troy and Albany among that group of municipalities quite smitten by the dam retaining much of the water that would have otherwise been cascading down their main streets during last week’s deluge.

Here’s a quick background. After centuries of flooding along the Hudson Valley, state engineers decided to “tame” one of its main tributaries, the Sacandaga River, which flows south through Hamilton County, then west through Fulton, Saratoga and Washington County before spilling into the Hudson.

To accomplish this, the state purchased the rights to 42-square miles of property in Fulton and Saratoga counties, which paved the way for the Conklingville Dam. This earthen embankment with a 400-foot-long concrete spillway blocked off the Sacandaga valley just west of Hadley and created the 29-mile long flood-control reservoir, which now holds back an average of more than 283 billion gallons of water.

That’s right, 283 billion gallons.

As could be expected with the creation of any giant lake came, soon came hordes of recreation seekers, who were already quite accustomed to basking in the Sacandaga. Very quickly, the state found itself in a quandary, owning miles of pristine shoreline for the regulation of the fluctuating reservoir and having more than 4,500 people wanting to buy portions of it for private use.

The solution was to create “lake access permits” so that the state could charge people to use the lake, but still retain rights to any land falling within seven feet of elevation from the lake’s maximum height of 768 feet above sea level. Also cashing in on the creation of the dam was a power company then called E.J. West, which built a hydroelectric facility on the northern bank of the dam nearby its spillway.

Was the history to end here, the story would conclude with a bunch of beach access permit holders being disgruntled over the fact that almost six feet of water has inundated their getaways and pulled away their beach furniture. This is a story in and of itself, simply because they’re paying for beach that is not there and to use a lake that is unsafe to navigate by boat, thanks to flood debris.

The real story, however, is

why the lake is so high right now. Ask the regulating district –the state public benefit corporation that controls the reservoir’s height –and they’re likely to cook up some song and dance about how they saved the lower Hudson Valley from become something akin to the Mohawk Valley last week.

In reality, the lake’s regulators have been squirreling away much more water in the reservoir ever since they penned the

40-year agreement with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in 2002. Simply put, FERC gave the green light for the regulating district to begin an “aggressive use of storage capacity” campaign, so that additional water could be released at times when the Hudson’s levels drop. This allows energy companies to make an extra buck whenever their power generating facilities along the Hudson are languishing, such as during the late Adirondack summers.

Here’s the problem. Both the dam and its spillway are now approaching the century mark in age. It’s not that either structure was constructed shoddy; in fact, the dam stands testament to the ingenuity of New York’s engineers of the early 20th century. But the fact remains, the dam

is growing older and

might not be able to go another 75 years if ran in the red by its overly exuberant regulators; after all, you don’t take grandpa’s

1927 Ford Model A for a spin on the freeway to see how long it can hold its top speed.

Then in May, it came out that the regulating district is

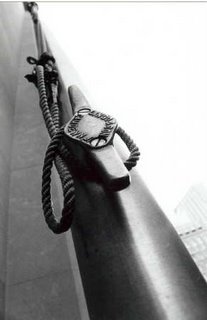

bidding for a $500,000 concrete renovation project near the power plant’s intake valves. The repairs were promulgated by a red flag issued by FERC last year –although both federal and state officials contend the work is “maintenance” related and has nothing to do with safety. Then again, FERC inspectors assessed the damage as needing “immediate repair,” in a letter sent to the district, which described the concrete on two piers as “eroded away” with steel rebar “exposed.”

And the repairs? They

were slated for this month. But with more than two feet of water pounding over the spillway, it’s not too likely the regulating district will get around to them anytime soon.

Were there a failure at the dam, the results would be catastrophic, if not apocalyptic. Municipalities such as Hadley and Corinth and Luzerne would be nothing more than an after thought. Flooding would be wide spread for miles around the Capital Region, as the lake drained. Granted, this is a very doomsday approach to the matter, but it’s one that should be heeded as the regulating district pushes the aging dam to its limits and beyond.

For those who were too busy spinning the turnstiles at the track Sunday, the celebrity watch has started: Hawk from the early 80s television sci-fi series Buck Rodgers.

For those who were too busy spinning the turnstiles at the track Sunday, the celebrity watch has started: Hawk from the early 80s television sci-fi series Buck Rodgers. Joining him was Fox 23’s John Gray, who’s best known for his nightly segment called Tool Time. Oh wait, that’s just his nightly newscast. And who could have a celebrity extravaganza without the Saratoga Racecourse's newly anointed Travers queen Yolanda Vega. Now that’s a lineup to draw out the paparazzi.

Joining him was Fox 23’s John Gray, who’s best known for his nightly segment called Tool Time. Oh wait, that’s just his nightly newscast. And who could have a celebrity extravaganza without the Saratoga Racecourse's newly anointed Travers queen Yolanda Vega. Now that’s a lineup to draw out the paparazzi. organizers to go back to the drawing board, because that’s a lineup that won’t raise much of anything other than questions like who the hell is Thom Christopher.

organizers to go back to the drawing board, because that’s a lineup that won’t raise much of anything other than questions like who the hell is Thom Christopher.

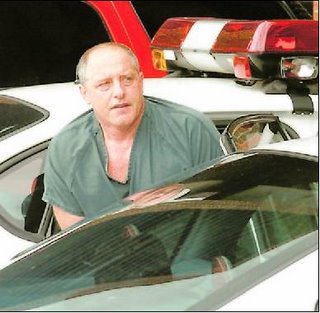

George Pataki

George Pataki